Barry Bonds built a Hall of Fame resume before he went to the Giants. But how would we remember him differently if he never left the Pittsburgh Pirates?

Barry Bonds should have presented his second act by now, right? His athletic contemporaries have settled into personas. Newly minted Hall of Famer David Ortiz is a grown-up, profane teddy bear; Alex Rodriguez, in recent years, has portrayed himself as a business dynamo. Before Kobe Bryant’s awful death in 2020, he was broadening his horizons, embarking on his second act as a father and filmmaker, pushing his 2003 rape allegation further into our memory banks.

The public has a remarkable ability to show tolerance, if not outright forgiveness, over an athlete’s indiscretions — if they have something resembling a personality.

Bonds has not swung a bat in a Major League game since 2007. You cannot sell tickets to a closed attraction.

A big part of modern celebrity is approachability, a concept Bonds never grasped. “I never saw a teammate care about him,” Bonds’s coach at Arizona State, Jim Brock, told Sports Illustrated in 1990. “Part of it would be his being rude, inconsiderate, and self-centered. He bragged about the money he had turned down, and he popped off about his dad [Barry Bonds]. I don’t think he ever figured out what to do to get people to like him.”

That didn’t improve in the pros. Pittsburgh Pirates‘ first baseman Sid Bream said at one point, according to Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams’s Game of Shadows, that “everybody in the Pittsburgh clubhouse had wanted to punch Barry out at one time or another.”

Derek Jeter, during his playing days, was enigmatic. Even when he described his five favorite movies, he did it with the enthusiasm of a hungover Blockbuster Video clerk working the morning shift. That’s okay. His cameo in The Other Guys aside, the man was so bland you could assign any designation. Old-timers could savor his role in continuing the Yankees tradition. Parents and young children found a role model. Analytics enthusiasts used him to show the fallacy of a high fielding percentage in rewarding Gold Gloves. Young men pondered his social life, though Mariah Carey filled in some of the blanks.

To me, a baseball fan, Bonds was a scowling, dynamic talent who was as opaque as 3 a.m. Dominance is wondrous, but it needs an entry point: Michael Jordan getting cut from his high school team; scrawny Tom Brady lingering in the 2000 NFL Draft; Aaron Rodgers getting cursed by Kenny Mayne. Without that wrinkle, greatness is robotic. Ask any NBA fan about the league’s review process: nobody who watches sports roots for the machines. The “doubters” trope in sportswriting exists for a reason, even though the people citing the doubters usually have unquestionable ability in their chosen sport. It’s relatable — who hasn’t been dismissed in their life? — and the likely foundation for another 20 years of athlete-produced documentaries.

Would Barry Bonds be a Hall-of-Famer if he never left the Pittsburgh Pirates?

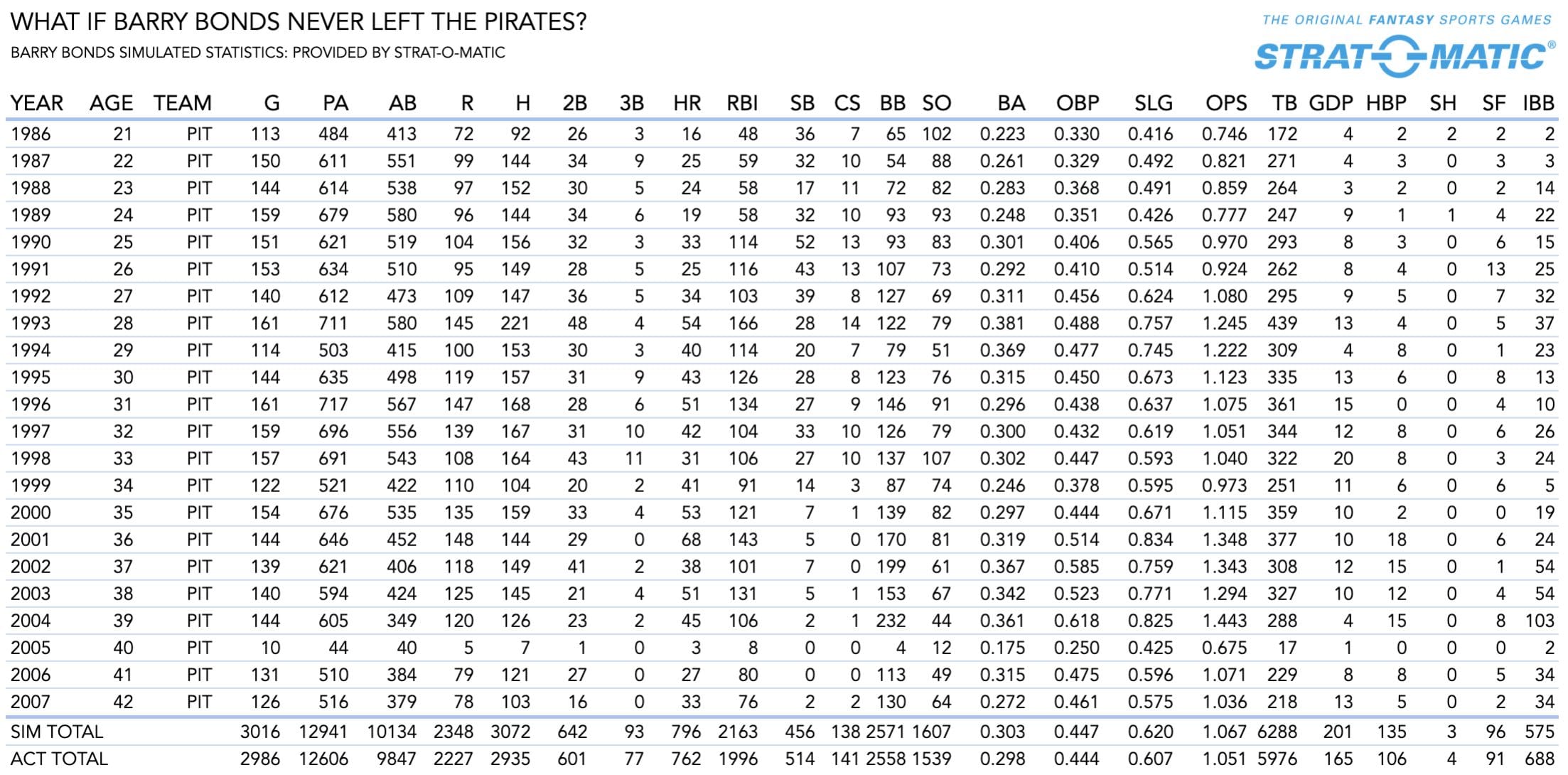

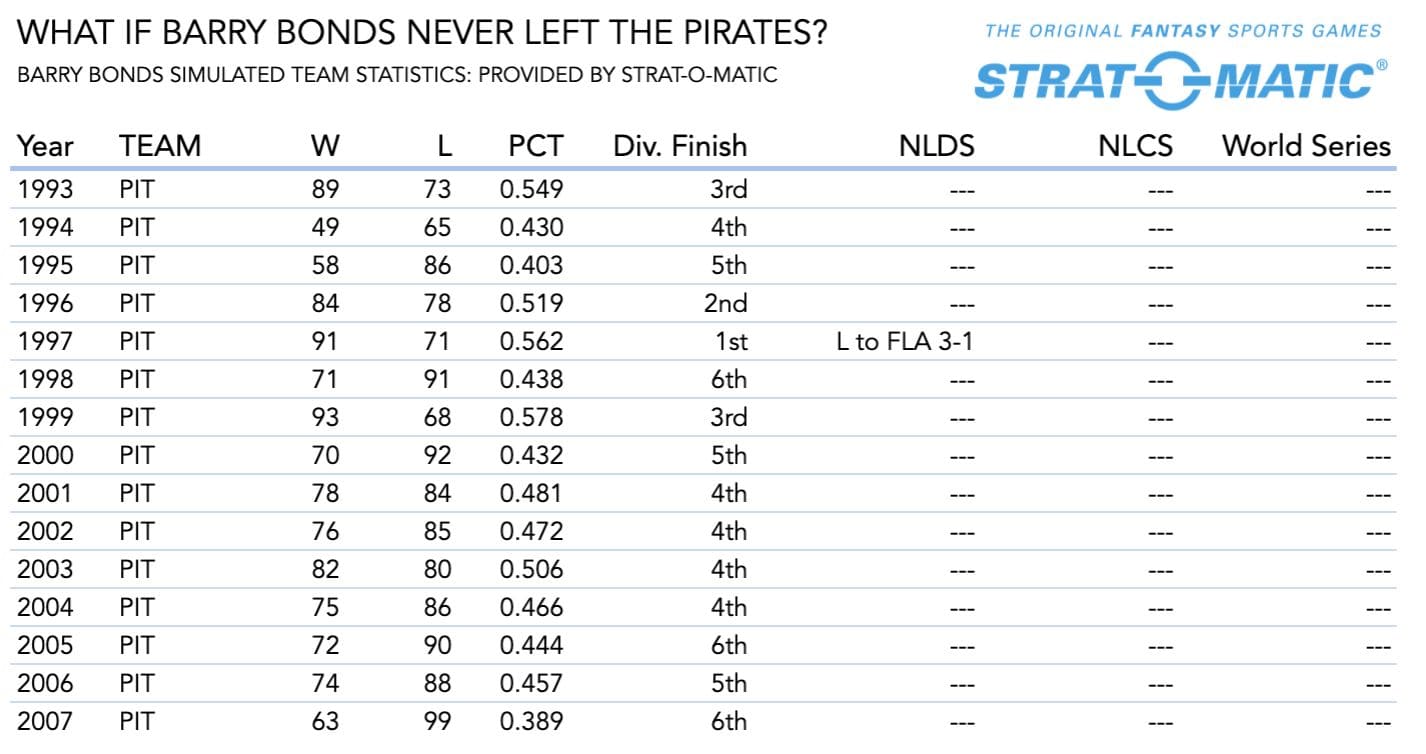

The question for this column is what Bonds’s career would have looked like if he had stayed with the cash-strapped Pittsburgh Pirates instead of signing with the San Francisco Giants. Before getting to the real matter at hand, here they are:

The numbers are similar to his years in San Francisco — zero championships and a gaudy number of homers. (Interestingly, Bonds doesn’t end up breaking Mark McGwire’s single-season homer mark in Pittsburgh.) The Pirates remain home for the World Series, their fans living off the disco-fueled memories of the 1979 “We are Family” team of Cobra and Pops.

But the numbers, both in real life and the ones provided by Strat-O-Matic, the Market Leaders in Sports Simulation, are irrelevant.

If you have the slightest appreciation for stats, they provide a hit of nostalgia. Man, Sidney Moncrief was a beast before the injuries. Wow, George Brett’s teams were fun to watch. Bonds’ numbers are depressing, and it has everything to do with the shadow cast by Greg Anderson, Victor Conte, and Bonds’s Michelin Man physique after 1998. It doesn’t matter if he stayed with the Pirates. The stats feel damaged, fraudulent. (Maybe Giants fans disagree. Hey, you do you!)

What needs to be reevaluated is his attitude. What if Barry Bonds resembled Ernie Banks or Ken Griffey, Jr. or another ebullient personality accompanied by an impish acoustic guitar solo in a Ken Burns’ documentary? What if he went the Derek Jeter route: answer the media’s questions and then disappear into a life straight from a men’s lifestyle glossy?

Here’s the question that needs to be answered, one that can’t be addressed with probabilities: If Barry Bonds had been loved beyond Giants fans, would the sports world have taken an interest?

Jeff Pearlman’s Love Me, Hate Me: Barry Bonds and the Making of an Antihero paints its subject as an egoistic talent who treated his teammates and the press with an equal amount of disdain. “The real truth,” Howard Bryant clarifies in his terrific Henry Aaron biography, The Last Hero, “was that Bonds treated Giants employees as badly as he did the writers.” He was obtuse in his quest for greatness, managing to anger the saintly Aaron. According to Bryant, the real home-run king hated that Bonds wanted to cash in on his legend during the latter’s sentiment-free 2007 all-time home run quest. “He’s trying to buy me,” Aaron told his confidants. “And I resent that.” Pearlman writes in his excellent book that if Bonds had said “Hey, I’ve made mistakes,” the public might have been eager to embrace him.

This is not about Bonds being a nice guy, but if he could have portrayed one. The ability to remember beat writers’ names—or in the case of Ortiz urging them “to go home and get some ass”— and deliver a pithy anecdote doesn’t make someone a humanitarian. Look at Pete Rose and O.J. Simpson.

Before Bonds emerged as a pharmaceutically concocted behemoth, he was Hall-of-Fame-bound. Look at his stats before 1999, when he arrived with 15 pounds of muscle to spring training and nobody thought it odd. The man was a talent: three MVPs, eight Gold Gloves, eight All-Star Games. If Harold Baines can get in, then Bonds pre-BALCO is a lock. What’s keeping him out of the Hall of Fame, according to Pearlman, is himself. If he were like Ortiz, the best-selling sports biographer told me, Bonds would be in the Hall of Fame. (Ortiz reportedly tested positive for an unspecified PED in 2003, something that has vanished in Red Sox lore along with Fever Pitch and Pumpsie Green.)

Entry into the Hall of Fame depends on votes. If you don’t think likability plays a role, get a clue. In Dan Patrick and Keith Olbermann’s book, The Big Show: A Tribute to ESPN’s SportsCenter, Olbermann describes how Rick Ferrell, a solid catcher during the 1930s and 1940s, made the hall. It was common practice for members of the Veterans Committee to cast “courtesy votes” as a favor or as a show of support. Well, in 1984, according to Olbermann, everyone cast a courtesy vote for Rick Ferrell. Whoops.

The Veterans Committee consists of old players, sportswriters, and executives — the kind of organization where Bonds should have friends. Acceptance of Bonds’ career and his impact on baseball history comes down to these members. The public’s judgment of Bonds won’t play a role, which is fitting for someone whose quest for glory was soulless, lonely, and profoundly sad.