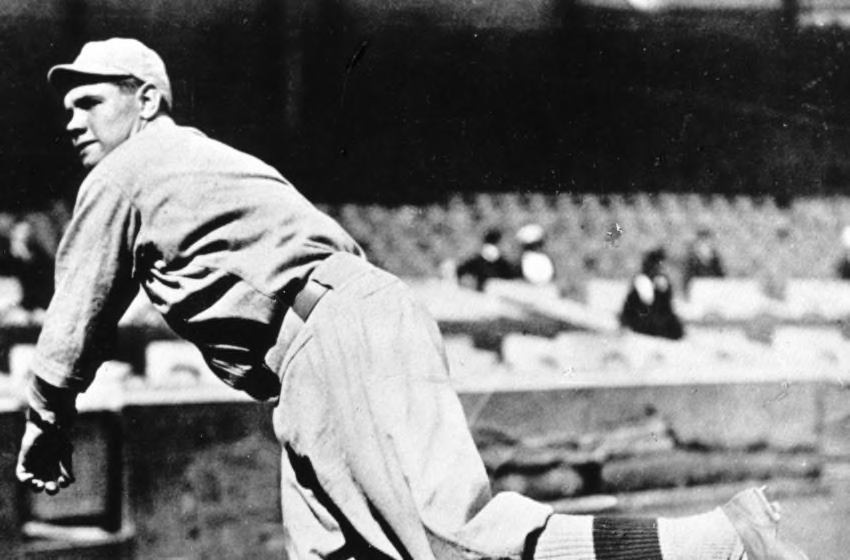

BOSTON – 1918. Babe Ruth, Boston Red Sox pitcher, warms up in Fenway Park before a contest in the 1918 season. (Photo by Mark Rucker/Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images)

A century before COVID-19, baseball and the United States had to contend with another devastating pandemic, the Spanish Flu, that nearly claimed the game’s biggest star.

Charles Conlon captured the essence of baseball’s ‘Dead Ball Era’ in one iconic photo. There is Ty Cobb, the best hitter in the game and most feared base runner, raising up a cloud of dust as he slides into third, his face a study in determination. Jimmy Austin, brave third baseman for the New York Highlanders, attempts both to tag him out and get out of the way of his sharp spikes. And in the background is umpire Francis H. O’Loughlin, ready to make a call in his booming voice.

NEW YORK, NY – 1912: Ty Cobb of the Detroit Tigers slides safely into third base past New York Yankees Jimmy Austin during a game at Hilltop Park in 1912 in New York City. (Photo Reproduction by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images)

‘Silk,’ as he was known on account of his childhood blonde curls, stood out among the colorful personalities of the game’s early years for his sense of style and flair. Batters became familiar with his trademark ‘Strike Tuh’ call, and he might have been the first umpire to use arm signals to make calls (although this fact is disputed).

He and Cobb couldn’t stay away from each other. O’Loughlin was the first umpire to eject Cobb from a game in 1908. But they also respected each other. In a May 1912 game at Hilltop Park, it was Cobb who guarded O’Loughlin against the bottles being rained onto the field by a rambunctious crowd after the umpire had ejected the Highlanders manager, pitcher, and catcher for arguing his balls and strikes. O’Loughlin was there to witness it all in the first two decades of the 20th century, from the brawling, the gambling, and, like Cobb, the legends making their mark on the game. He was behind the plate for six no-hitters, still the most by an umpire, and called five World Series between 1906 and 1917.

But not even Cobb could protect O’Loughlin from the ravages of the Spanish Flu epidemic. He died in December 1918 at his Boston home, his career cut short at the age of 46. He was only one of the 50 million worldwide and 675,000 in the United States who succumbed to the disease. Baseball was not immune: Larry Chappell, an outfielder for the White Sox, Indians, and Braves between 1913-1917, died in November; so did Cy Swain, who once hit 37 home runs in one season in the minors; Harry Glenn, a former catcher with the Cardinals, died in October. Fortunately for baseball posterity, though, it didn’t claim a young southpaw pitcher for the Boston Red Sox.

In the spring of 1918, with the war still raging in Europe and able-bodied men needed for the armed forces, President Woodrow Wilson ordered the Major Leagues to finish by Sept. 1. The Red Sox, world champions two of the last three seasons, had 13 players enlist. New manager Ed Barrow needed to find replacements for his star batters and found one in an unlikely place: pitcher George Herman ‘Babe’ Ruth.

The 23-year-old Ruth was an established pitcher, winning 65 games with a 2.02 ERA the previous three seasons. Already during spring training rumors of his prowess with the bat began circulating. An exhibition against the Dodgers in March at Camp Pike in Arkansas was canceled due to rain, but the players stayed around to take batting practice. Ruth, unleashing his powerful upper-cut swing, sent five balls over the fence. The headline the next day in the Boston American newspaper read: “Babe Ruth Puts Five Over Fence, Heretofore Unknown to Baseball Fans.” Barrow had found the man who would put people in the seats at Fenway Park.

Something else spread through Red Sox camp that spring. Several players came down with a mysterious illness. Ruth was spared, but not for long. On May 19, he began complaining about a fever and body aches, his temperature rising to 104 degrees. Doctors prescribed silver nitrate, which only made his symptoms worse. Soon, as Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith write in their book War Fever: Boston, Baseball, and America in the Shadow of the Great War, news came out that “the Colossus…worth more than his weight in gold” was dying.

Those fears proved short-lived, and within a few days, Ruth made a full recovery. Barrow had begun playing him in the field on days Ruth didn’t pitch; in a game on May 6 in New York, Barrow put Ruth fifth in the order, the first time he had ever batted anywhere but ninth. In June, Ruth hit eight home runs. He ended the year tied with the Athletics’ Tillie Walker for the league-lead with 11, more than five teams and the first of 12 times Ruth would lead the league in homers. He also won 13 games on the mound.

The Red Sox finished atop the American League with 75 wins and earned a trip to the World Series against the Chicago Cubs. The first three games were scheduled to be played at Comiskey Park before making the move to Boston. But that same week, sailors returning from overseas had brought back the Spanish Flu.

Health officials advised against holding large public gatherings—like baseball games—to stop the spread of a disease that was already devastating Boston. The games went ahead, though, with more than 60,000 packing Fenway Park for Games 4-6.

Ruth had a great series, winning two games on the mound and extending his consecutive scoreless innings streak in the World Series to 29.2, a record that stood for 43 years. The Red Sox won in six games, but with Americans still dying in Europe, the city in the midst of a pandemic, and players bickering over gate receipts, few seemed to care.

“It was as anticlimatic as a game could be. No celebration in the stands. No celebration on the field. It was almost as if everyone was happy just to get it over with,” wrote Skip Desjardin in September 1918: War, Plague, and the World Series.

Little did Red Sox fans know that it would be another 86 years before they won the championship again.

After the World Series, Boston became an epicenter of the pandemic. By the end of the year, more than 20 percent of the city’s population had fallen ill and 5,000 Bostonians had died, including O’Loughlin. Ruth contracted the disease again in October but recovered. O’Loughlin and thousands of others weren’t as lucky.

Ruth, of course, would go on to become “The Bambino,” the “Sultan of Swat,” the biggest star in the game’s history. But, due to the Spanish Flu, it almost never happened. As baseball prepares to resume play amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it can take some lessons from what happened a century ago. Baseball is America’s pastime, but it’s intrinsically tied to America’s problems.